Inequality a Reassessment of the Effects of Family and Schooling in America

Furnishings of income inequality, researchers have found, include higher rates of health and social problems, and lower rates of social goods,[1] a lower population-wide satisfaction and happiness[2] [3] and fifty-fifty a lower level of economic growth when human capital is neglected for high-end consumption.[iv] For the top 21 industrialised countries, counting each person equally, life expectancy is lower in more unequal countries (r = -.907).[5] A similar relationship exists amid US states (r = -.620).[6]

2013 Economics Nobel prize winner Robert J. Shiller said that ascension inequality in the United States and elsewhere is the nearly important problem.[7]

Health [edit]

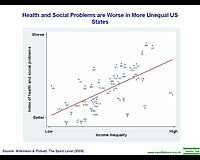

Wellness and social issues are worse in more unequal countries and in more unequal United states states, though the reason for this correlation remains debated. The income inequality of countries is the 20:xx ratio measure of income inequality from the United nations Development Programme Human Development Indicators, 2003-vi and for states information technology is the 1999 Gini index.

British researchers Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett take establish higher rates of health and social problems (obesity, mental illness, homicides, teenage births, incarceration, kid conflict, drug use), and lower rates of social appurtenances (life expectancy by land, educational performance, trust amidst strangers, women'southward status, social mobility, even numbers of patents issued) in countries and states with higher inequality. Using statistics from 23 developed countries and the 50 states of the United states, they found social/wellness bug lower in countries similar Japan and Finland and states like Utah and New Hampshire with loftier levels of equality, than in countries (US and UK) and states (Mississippi and New York) with large differences in household income.[viii] [ix]

For well-nigh of man history higher fabric living standards – total stomachs, access to make clean water and warmth from fuel – led to amend wellness and longer lives.[1] This blueprint of college incomes-longer lives still holds among poorer countries, where life expectancy increases apace as per capita income increases, only in recent decades it has slowed downwardly among middle income countries and plateaued amid the richest 30 or and then countries in the world.[10] Americans live no longer on average (nearly 77 years in 2004) than Greeks (78 years) or New Zealanders (78), though the The states has a higher Gdp per capita. Life expectancy in Sweden (eighty years) and Japan (82) – where income was more equally distributed – was longer.[11] [12]

In contempo years the characteristic that has strongly correlated with health in developed countries is income inequality. Creating an alphabetize of "Health and Social Problems" from nine factors, authors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett institute health and social problems "more than common in countries with bigger income inequalities",[thirteen] [14] and more common amidst states in the U.s. with larger income inequalities.[15] Other studies accept confirmed this relationship. The UNICEF index of "child well-being in rich countries", studying twoscore indicators in 22 countries, correlates with greater equality simply not per capita income.[16] Pickett and Wilkinson fence that inequality and social stratification atomic number 82 to higher levels of psychosocial stress and status feet which can lead to depression, chemical dependency, less community life, parenting problems and stress-related diseases.[17]

In their book, Social Epidemiology, Ichiro Kawachi and Due south.V. Subramanian establish that impoverished individuals simply cannot lead good for you lives as easily as the wealthy. They are unable to secure adequate nutrition for their families, cannot pay utility bills to keep themselves warm during the winter or cold during estrus waves, and lack sufficient housing.[xviii] In an article by the Mutual Wealth Fund, Peter J. Cunningham states that 26% of lower-income people are uninsured compared to 4% of college income people. This lack of medical resources leads more lower-income individuals to non obtaining essential prescription medication or the ability to pay off medical bills. Cunningham proposes even if low-income individuals are able to get medical care outside sources such every bit poor housing tin can however detriment their health and so he proposes health care providers to find ways to meet these patients with more than sufficient treatment. [19]

National income inequality is positively related to the land'south rate of schizophrenia.[20] Information technology has been suggested contempo decline in life expectancy in the The states is linked to extreme inequality.[21]

Conversely, some researchers have criticised the view that economic inequality causes worse health outcomes, with some studies failing to confirm the relationship or finding that the relationship was more complicated due to issues of determining causality, inadequate data, correlation versus causation or confounding variables (for example, more diff countries tend to be economically poorer).[22] [23] [24] [25] [26]

[edit]

Research has shown an inverse link between income inequality and social cohesion. In more equal societies, people are much more likely to trust each other, measures of social uppercase (the benefits of goodwill, fellowship, mutual sympathy and social connexion among groups who make upwards a social units) suggest greater community interest, and homicide rates are consistently lower[ citation needed ].

Comparing results from the question "would others take advantage of you if they got the chance?" in U.Southward General Social Survey and statistics on income inequality, Eric Uslaner and Mitchell Brownish plant there is a high correlation between the amount of trust in gild and the amount of income equality.[27] A 2008 article by Andersen and Fetner likewise found a potent relationship between economic inequality within and across countries and tolerance for 35 democracies.

In two studies Robert Putnam established links betwixt social capital and economic inequality. His nearly important studies[28] [29] established these links in both the United States and in Italy. His explanation for this relationship is that

Community and equality are mutually reinforcing... Social capital letter and economic inequality moved in tandem through most of the twentieth century. In terms of the distribution of wealth and income, America in the 1950s and 1960s was more egalitarian than it had been in more than a century... [T]hose same decades were also the high point of social connexion and borough engagement. Record highs in equality and social capital coincided. Conversely, the last third of the twentieth century was a time of growing inequality and eroding social capital... The timing of the ii trends is striking: somewhere around 1965–lxx America reversed course and started condign both less merely economically and less well connected socially and politically.[30]

Albrekt Larsen has advanced this explanation past a comparative study of how trust increased in Denmark and Sweden in the latter office of the 20th century while information technology decreased in the U.s.a. and Great britain. It is argued that inequality levels influence how citizens imagine the trustworthiness of fellow citizens. In this model social trust is not well-nigh relations to people you meet (as in Putnam'south model) but about people you imagine.[31]

The economist Joseph Stiglitz has argued that economic inequality has led to distrust of business concern and government.[32]

Crime [edit]

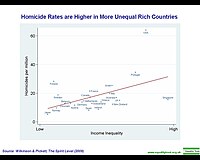

Homicide rates are higher in more than unequal rich countries or in more unequal The states states

Criminal offence rate has also been shown to be correlated with inequality in gild. Nigh studies looking into the relationship accept concentrated on homicides – since homicides are well-nigh identically defined across all nations and jurisdictions. Daly et al. 2001 estimated that near one-half of all variation in homicide rates amid U.S. states and Canadian provinces tin be accounted for by differences in the amount of inequality in each province or country.[33] Fajnzylber et al. (2002) found a similar relationship worldwide. Among comments in bookish literature on the relationship between homicides and inequality are:

- The most consistent finding in cross-national research on homicides has been that of a positive association between income inequality and homicides.[34]

- Economic inequality is positively and significantly related to rates of homicide despite an all-encompassing list of conceptually relevant controls. The fact that this relationship is found with the most recent data and using a unlike mensurate of economic inequality from previous research, suggests that the finding is very robust.[35]

A 2016 study, controlling for different factors than previous studies, challenges the aforementioned findings. The study finds "little evidence of a pregnant empirical link between overall inequality and criminal offence", and that "the previously reported positive correlation between violent criminal offense and economic inequality is largely driven by economical segregation across neighborhoods instead of within-neighborhood inequality".[36] A 2020 written report establish that in Europe, the inequality-crime correlation was nowadays simply weak (0.10), explaining less than iii% of the variance in criminal offense[37] with a similar finding occurring for the United States,[38] while another 2019 written report argued that the result of inequality on property crime was nearly zero.[39]

Redistribution and welfare [edit]

Child well-being is better in more equal rich countries

Following the utilitarian principle of seeking the greatest good for the greatest number – economic inequality is problematic. A house that provides less utility to a millionaire every bit a summer home than information technology would to a homeless family of five, is an instance of reduced "distributive efficiency" within society, that decreases marginal utility of wealth and thus the sum full of personal utility. An additional dollar spent past a poor person volition get to things providing a keen bargain of utility to that person, such as basic necessities like food, h2o, and healthcare; while, an additional dollar spent by a much richer person volition very likely become to luxury items providing relatively less utility to that person. Thus, the marginal utility of wealth per person ("the additional dollar") decreases as a person becomes richer. From this standpoint, for whatever given amount of wealth in society, a society with more equality volition accept higher aggregate utility. Some studies[2] [3] have found bear witness for this theory, noting that in societies where inequality is lower, population-wide satisfaction and happiness tend to be higher.

Philosopher David Schmidtz argues that maximizing the sum of individual utilities volition harm incentives to produce.

A social club that takes Joe Rich's 2nd unit of measurement [of corn] is taking that unit of measurement away from someone who . . . has nix better to practice than plant information technology and giving it to someone who . . . does take something meliorate to do with information technology. That sounds good, just in the process, the society takes seed corn out of product and diverts information technology to food, thereby cannibalizing itself.[40]

Notwithstanding, in addition to the diminishing marginal utility of diff distribution, Pigou and others signal out that a "keeping up with the Joneses" effect amongst the well off may atomic number 82 to greater inequality and use of resource for no greater return in utility.

a larger proportion of the satisfaction yielded past the incomes of rich people comes from their relative, rather than from their absolute, amount. This part of it volition not exist destroyed if the incomes of all rich people are diminished together. The loss of economic welfare suffered by the rich when control over resource is transferred from them to the poor will, therefore, be essentially smaller relatively to the gain of economic welfare to the poor than a consideration of the police of diminishing utility taken by itself suggests.[41]

When the goal is to ain the biggest yacht – rather than a boat with certain features – there is no greater benefit from owning 100 metre long boat than a 20 m one every bit long every bit information technology is bigger than your rival.

Economist Robert H. Frank compare the situation to that of male elks who use their antlers to spar with other males for mating rights.

The pressure to have bigger ones than your rivals leads to an arms race that consumes resource that could accept been used more efficiently for other things, such as fighting off disease. As a consequence, every male ends up with a cumbersome and expensive pair of antlers, ... and "life is more miserable for bull elk equally a grouping."[42]

Firstly, sure costs are difficult to avoid and are shared past everyone, such every bit the costs of housing, pensions, education and health care. If the country does not provide these services, then for those on lower incomes, the costs must be borrowed and often those on lower incomes are those who are worse equipped to manage their finances. Secondly, aspirational consumption describes the procedure of middle income earners aspiring to reach the standards of living enjoyed by their wealthier counterparts and ane method of achieving this aspiration is past taking on debt. The result leads to even greater inequality and potential economic instability.[43]

Poverty [edit]

Oxfam asserts that worsening inequality is impeding the fight against global poverty. A 2013 written report from the group stated that the $240 billion added to the fortunes of the world's richest billionaires in 2012 was enough to end extreme poverty four times over. Oxfam Executive Manager Jeremy Hobbs said that "We can no longer pretend that the cosmos of wealth for a few volition inevitably do good the many – too often the opposite is true."[44] [45] [46] The 2018 Oxfam written report said that the income of the globe's billionaires in 2017, $762 billion, was enough to end extreme global poverty seven times over.[47]

Jared Bernstein and Elise Gould of the Economic Policy Found suggest that poverty in the United States could accept been significantly mitigated if inequality had not increased over the last few decades.[48] [49]

Housing [edit]

Ran down housing complex in Brazil.

Ran downwards houses in Cape Town, Due south Africa with residents sitting outside.

In many poor and developing countries, much country and housing is held exterior the formal or legal property ownership registration organization. Much unregistered belongings is held in breezy form through various associations and other arrangements. Reasons for actress-legal ownership include excessive bureaucratic red tape in buying property and building, In some countries it can take over 200 steps and upwardly to xiv years to build on government land. Other causes of extra-legal property are failures to notarize transaction documents or having documents notarized but declining to accept them recorded with the official agency.[50]

Rent controls in Brazil dramatically reduced the percent of legal housing compared to extra-legal housing, which had a much amend supply to demand balance.[50]

A number of researchers (David Rodda,[51] Jacob Vigdor,[52] and Janna Matlack), debate that a shortage of affordable housing – at least in the U.s.a. – is caused in part by income inequality.[53] David Rodda[51] [54] noted that from 1984 and 1991, the number of quality rental units decreased equally the need for higher quality housing increased (Rhoda 1994:148).[51]

Aggregate need, consumption and debt [edit]

Conservative researchers have argued that income inequality is not significant because consumption, rather than income should be the measure of inequality, and inequality of consumption is less extreme than inequality of income in the U.s.a.. Co-ordinate to Johnson, Smeeding, and Tory, consumption inequality was actually lower in 2001 than it was in 1986.[55] [56] The debate is summarized in "The Hidden Prosperity of the Poor" by journalist Thomas B. Edsall.[57] Other studies have not found consumption inequality less dramatic than household income inequality,[58] [59] and the CBO's written report plant consumption data not "adequately" capturing "consumption by loftier-income households" every bit it does their income, though information technology did agree that household consumption numbers bear witness more equal distribution than household income.[60]

Others dispute the importance of consumption over income, pointing out that if heart and lower income are consuming more than they earn it is because they are saving less or going deeper into debt.[61] Income inequality has been the driving factor in the growing household debt,[58] [62] as high earners bid up the price of real estate and eye income earners go deeper into debt trying to maintain what in one case was a middle class lifestyle.[63]

Central Banking economist Raghuram Rajan argues that "systematic economic inequalities, within the The states and effectually the world, take created deep financial 'error lines' that accept fabricated [financial] crises more likely to happen than in the by" – the Fiscal crisis of 2007–08 being the about recent instance.[64] To compensate for stagnating and declining purchasing power, political pressure has developed to extend easier credit to the lower and center income earners – peculiarly to buy homes – and easier credit in general to keep unemployment rates low. This has given the American economy a trend to go "from bubble to bubble" fueled by unsustainable monetary stimulation.[65]

Monopolization of labor, consolidation, and contest [edit]

Greater income inequality can atomic number 82 to monopolization of the labor strength, resulting in fewer employers requiring fewer workers.[66] Remaining employers can consolidate and take advantage of the relative lack of competition, leading to less consumer option, market abuses, and relatively higher existent prices.[67] [66]

Economic incentives [edit]

Some economists believe that i of the principal reasons that inequality might induce economic incentive is because material well-being and conspicuous consumption chronicle to status. In this view, loftier stratification of income (high inequality) creates loftier amounts of social stratification, leading to greater contest for status.

1 of the first writers to annotation this relationship, Adam Smith, recognized "regard" as one of the major driving forces behind economic activity. From The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759:

[Due west]lid is the end of avarice and ambition, of the pursuit of wealth, of power, and pre-eminence? Is it to supply the necessities of nature? The wages of the meanest labourer can supply them... [Westward]hy should those who have been educated in the higher ranks of life, regard it as worse than death, to be reduced to alive, even without labour, upon the same simple fare with him, to dwell under the same lowly roof, and to exist clothed in the same humble attire? From whence, then, arises that emulation which runs through all the different ranks of men, and what are the advantages which we propose by that great purpose of human life which we call bettering our status? To exist observed, to exist attended to, to be taken observe of with sympathy, complacency, and approbation, are all the advantages which we tin can propose to derive from information technology. It is the vanity, not the ease, or the pleasure, which interests us.[68]

Modern sociologists and economists such every bit Juliet Schor and Robert H. Frank take studied the extent to which economic action is fueled by the power of consumption to represent social condition. Schor, in The Overspent American, argues that the increasing inequality during the 1980s and 1990s strongly accounts for increasing aspirations of income, increased consumption, decreased savings, and increased debt.

In the book Luxury Fever, Robert H. Frank argues that satisfaction with levels of income is much more strongly affected by how someone's income compares with others than its absolute level. Frank gives the instance of instructions to a yacht architect by a customer – shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos – to make Niarchos' new yacht 50 feet longer than that of rival magnate Aristotle Onassis. Niarchos did not specify or reportedly even know the exact length of Onassis's yacht.[69] [70]

Economic growth [edit]

Theories [edit]

The prevailing views about the role of inequality in the growth procedure has radically shifted in the past century.[71]

The classical perspective, as expressed by Adam Smith, and others, suggests that inequality fosters the growth process.[72] [73] Specifically, since the aggregate saving increases with inequality due to higher propensity to salvage among the wealthy, the classical viewpoint suggests that inequality stimulates capital letter accumulation and therefore economic growth.[74]

The Neoclassical perspective that is based on representative amanuensis approach denies the role of inequality in the growth process. Information technology suggests that the while the growth procedure may bear upon inequality, income distribution has no impact on the growth process.

The modern perspective which has emerged in the tardily 1980s suggests, in contrast, that income distribution has a significant impact on the growth process. The modernistic perspective, originated by Galor and Zeira,[75] [76] highlights the important role of heterogeneity in the determination of aggregate economical activity, and economic growth. In particular, Galor and Zeira argue that since credit markets are imperfect, inequality has an enduring impact on human capital letter formation, the level of income per capita, and the growth procedure.[77] In contrast to the classical paradigm, which underlined the positive implications of inequality for capital formation and economical growth, Galor and Zeira contend that inequality has an adverse effect on human capital germination and the development process, in all only the very poor economies.

Later theoretical developments have reinforced the view that inequality has an adverse effect on the growth process. Specifically, Alesina and Rodrik and Persson and Tabellini advance a political economy mechanism and contend that inequality has a negative impact on economical development since it creates a pressure for distortionary redistributive policies that have an adverse event on investment and economic growth.[78]

A unified theory of inequality and growth that captures that changing office of inequality in the growth process offers a reconciliation betwixt the conflicting predictions of classical viewpoint that maintained that inequality is benign for growth and the modern viewpoint that suggests that in the presence of credit market imperfections, inequality predominantly results in nether investment in human being capital letter and lower economic growth. This unified theory of inequality and growth, adult past Oded Galor and Omer Moav,[80] suggests that the consequence of inequality on the growth procedure has been reversed as human being capital has replaced concrete capital as the main engine of economic growth. In the initial phases of industrialization, when physical majuscule accumulation was the dominating source of economical growth, inequality additional the evolution procedure by directing resource toward individuals with higher propensity to salvage. However, in later phases, equally human capital became the main engine of economical growth, more than equal distribution of income, in the presence of credit constraints, stimulated investment in human being majuscule and economic growth.

Evidence [edit]

The reduced form empirical relationship between inequality and growth was studies by Alberto Alesina and Dani Rodrik,[78] and Torsten Persson and Guido Tabellini. They find that inequality is negatively associated with economical growth in a cross-country analysis.

A 1999 review in the Journal of Economic Literature states loftier inequality lowers growth, perhaps considering it increases social and political instability.[81] The article also says:

Somewhat unusually for the growth literature, studies have tended to concur in finding a negative result of high inequality on subsequent growth. The evidence has not been accepted by all: some writers point out the concentration of richer countries at the lower terminate of the inequality spectrum, the poor quality of the distribution data, and the lack of robustness to stock-still effects specifications. At to the lowest degree, though, it has go extremely difficult to build a case that inequality is practiced for growth. This in itself represents a considerable advance. Given the indications that inequality is harmful for growth, attention has moved on to the likely mechanisms.... the literature seems to exist moving ... towards an examination of the effects of inequality on fertility rates, investment in education, and political stability.[81]

A 1992 World Depository financial institution written report published in the Journal of Development Economics said that

Inequality is negatively, and robustly, correlated with growth. This result is non highly dependent upon assumptions about either the form of the growth regression or the measure out of inequality...Although statistically meaning, the magnitude of the human relationship between inequality and growth is relatively small.[82]

NYU economist William Baumol institute that substantial inequality does not stimulate growth considering poverty reduces labor forcefulness productivity.[83] Economists Dierk Herzer and Sebastian Vollmer found that increased income inequality reduces economic growth, only growth itself increases income inequality.[84]

Berg and Ostry of the International Monetary Fund found that of the factors affecting the elapsing of growth spells (not the rate of growth) in developed and developing countries, income equality is more beneficial than trade openness, sound political institutions, or foreign investment.[85] [86]

A 1996 study past Perotti examined the channels through which inequality may bear upon economic growth. He showed that, in accordance with the credit market place imperfection approach, inequality is associated with lower level of human uppercase formation (education, experience, and apprenticeship) and higher level of fertility, and thereby lower levels of growth. He found that inequality is associated with higher levels of redistributive revenue enhancement, which is associated with lower levels of growth from reductions in individual savings and investment. Perotti concluded that, "more equal societies take lower fertility rates and higher rates of investment in education. Both are reflected in higher rates of growth. Also, very unequal societies tend to be politically and socially unstable, which is reflected in lower rates of investment and therefore growth."[87]

Robert Barro reexamined the reduced grade relationship between inequality on economic growth in a console of countries.[88] He argues that there is "niggling overall relation betwixt income inequality and rates of growth and investment." However, his empirical strategy limits its applicability to the understanding of the relationship betwixt inequality and growth for several reasons. Get-go, his regression analysis control for education, fertility, investment, and information technology therefore excludes, by structure, the important effect of inequality on growth via teaching, fertility, and investment. His findings just imply that inequality has no direct consequence on growth beyond the of import indirect effects through the principal channels proposed in the literature. Second his study analyzes the effect of inequality on the average growth rate in the following 10 years. However, existing theories advise that the upshot of inequality will exist observed much later, equally is the instance in human being capital formation, for instance. Third, the empirical analysis does not business relationship for biases that are generated by reverse causality and omitted variables.

A report of Swedish counties between 1960 and 2000 found a positive impact of inequality on growth with lead times of five years or less, just no correlation after ten years.[89] Studies of larger data sets accept institute no correlations for any fixed atomic number 82 time,[xc] and a negative impact on the elapsing of growth.[85]

Some theories developed in the 1970s established possible avenues through which inequality may have a positive effect on economical development.[85] [86] According to a 1955 review, savings by the wealthy, if these increment with inequality, were thought to first reduced consumer need.[91]

Co-ordinate to International Monetary Fund economists, inequality in wealth and income is negatively correlated with the duration of economic growth spells (not the rate of growth).[85] High levels of inequality foreclose not only economic prosperity, but also the quality of a country'due south institutions and high levels of education.[92] Co-ordinate to International monetary fund staff economists, "if the income share of the top twenty percent (the rich) increases, then GDP growth actually declines over the medium term, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down. In dissimilarity, an increment in the income share of the bottom 20 pct (the poor) is associated with higher Gross domestic product growth. The poor and the middle class matter the about for growth via a number of interrelated economic, social, and political channels."[93]

Even so, farther piece of work done in 2015 by Sutirtha Bagchi and Jan Svejnar suggests that it is just inequality caused past corruption and cronyism that harms growth. When they control for the fact that some inequality is caused past billionaires using their political connections, then inequality acquired by market forces does not seem to have an event on growth.[94]

Economist Joseph Stiglitz presented evidence in 2009 that both global inequality and inequality within countries foreclose growth by limiting amass demand.[95] Economist Branko Milanovic, wrote in 2001 that, "The view that income inequality harms growth – or that improved equality tin help sustain growth – has become more than widely held in recent years. ... The main reason for this shift is the increasing importance of human capital in evolution. When physical capital mattered most, savings and investments were key. Then it was important to have a large contingent of rich people who could save a greater proportion of their income than the poor and invest it in physical capital. But now that human majuscule is scarcer than machines, widespread educational activity has become the clandestine to growth."[4]

Studies on income inequality and growth have sometimes constitute evidence confirming the Kuznets curve hypothesis, which states that with economic evolution, inequality first increases, then decreases.[82] Economist Thomas Piketty challenges this notion, claiming that from 1914 to 1945 wars and "vehement economic and political shocks" reduced inequality. Moreover, Piketty argues that the "magical" Kuznets curve hypothesis, with its emphasis on the balancing of economical growth in the long run, cannot business relationship for the significant increase in economic inequality throughout the developed world since the 1970s.[96] Withal, Kristin Forbes plant that if country-specific effects were eliminated past using panel estimation, then income inequality does take a significant positive relationship with economic growth. This relationship held across different "samples, variable definitions, and model specifications."[97] Historian Walter Scheidel, who builds on Piketty'southward thesis that it has been trigger-happy shocks that accept reduced inequality in The Great Leveler (2017), contends that "the preponderance of the bear witness fails to support the idea of a systematic relationship betwixt economic growth and income inequality as first envisioned past Kuznets sixty years ago."[98]

A 2012 study published by Inyong Shin of Asia University plant that economic inequality in the developed earth has a very different event on economic growth than in the developing world, saying that "higher inequality tin can retard growth in the early phase of economical development", only that "college inequality can encourage growth in a almost steady state".[99]

A 2013 report on Nigeria suggests that growth has risen with increased income inequality.[100] Some theories popular from the 1950s to 2011 argued that inequality had a positive effect on economic development.[85] [86] However, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo fence that analyses based on comparing yearly equality figures to yearly growth rates were misleading because it takes several years for furnishings to manifest equally changes to economic growth.[ninety] Imf economists found a strong association betwixt lower levels of inequality in developing countries and sustained periods of economic growth. Developing countries with high inequality have "succeeded in initiating growth at high rates for a few years" but "longer growth spells are robustly associated with more than equality in the income distribution."[86]

An OECD study in 2015, found that internationally "countries where income inequality is decreasing abound faster than those with rising inequality", and noted that "a lack of investment in education past the poor is the main factor behind inequality hurting growth"[101]

A 2016 meta-analysis constitute that "the result of inequality on growth is negative and more pronounced in less developed countries than in rich countries", though the average impact on growth was not significant. The report also found that wealth, state and human uppercase inequality is more pernicious to growth than income inequality.[102]

A 2017 written report argued that there were both positive and negative effects of inequality: "When inequality is associated with political instability and social unrest, rent-seeking and distortive policies, lower capacities for investment in man capital letter, and a stagnant domestic marketplace, it is mostly expected to impairment long-run economical operation, as suggested by many authors. Accordingly, improving income distribution is expected to foster long-run economic growth, especially in low-income countries where the levels of inequality are ordinarily very high. Notwithstanding, some degree of inequality can besides be good, as has been theoretically argued in the literature and as empirically suggested in this study. A degree of inequality tin can play a beneficial role for economical growth when that inequality is driven past market forces and related to hard work and growth-enhancing incentives like risk taking, innovation, capital letter investment, and agglomeration economies. The challenge for policy makers is to control structural inequality, which reduces the country's capacities for economic development, while at the same time keeping in identify those positive incentives that are besides necessary for growth."[103]

Mechanisms [edit]

The Galor and Zeira'due south model predicts that the effect of rise inequality on Gross domestic product per capita is negative in relatively rich countries just positive in poor countries.[75] [76] These testable predictions have been examined and confirmed empirically in recent studies.[104] [105] In particular, Brückner and Lederman test the prediction of the model by in the panel of countries during the menstruum 1970–2010, by because the impact of the interaction between the level of income inequality and the initial level of Gross domestic product per capita. In line with the predictions of the model, they observe that at the 25th percentile of initial income in the earth sample, a 1 per centum point increase in the Gini coefficient increases income per capita by 2.3%, whereas at the 75th percentile of initial income a ane percent point increase in the Gini coefficient decreases income per capita past -v.3%. Moreover, the proposed homo capital letter mechanism that mediate the effect of inequality on growth in the Galor-Zeira model is also confirmed. Increases in income inequality increase human upper-case letter in poor countries but reduce it in high and middle-income countries.

This recent support for the predictions of the Galor-Zeira model is in line with earlier findings. Roberto Perotti showed that in accordance with the credit marketplace imperfection arroyo, developed past Galor and Zeira, inequality is associated with lower level of homo capital formation (education, feel, apprenticeship) and college level of fertility, while lower level of homo capital is associated with lower levels of economic growth.[106] Princeton economist Roland Benabou's finds that the growth process of Korea and the Philippines "are broadly consistent with the credit-constrained homo-uppercase accumulation hypothesis."[107] In improver, Andrew Berg and Jonathan Ostry suggest that inequality seems to impact growth through human majuscule accumulation and fertility channels.[108]

In contrast, Perotti argues that the political economy mechanism is not supported empirically. Inequality is associated with lower redistribution, and lower redistribution (nether-investment in educational activity and infrastructure) is associated with lower economical growth.[106]

Co-ordinate to economist Branko Milanovic, while traditionally economists thought inequality was adept for growth

The view that income inequality harms growth – or that improved equality can help sustain growth – has become more widely held in recent years. ... The main reason for this shift is the increasing importance of human capital in development. When concrete capital mattered most, savings and investments were key. And so information technology was important to accept a large contingent of rich people who could relieve a greater proportion of their income than the poor and invest information technology in physical majuscule. But now that human being capital is scarcer than machines, widespread pedagogy has become the cloak-and-dagger to growth.[iv]

"Broadly accessible education" is both difficult to accomplish when income distribution is uneven and tends to reduce "income gaps between skilled and unskilled labor."

The sovereign-debt economic problems of the late 20-oughts do not seem to be correlated to redistribution policies in Europe. With the exception of Ireland, the countries at risk of default in 2011 (Greece, Italy, Kingdom of spain, Portugal) were notable for their high Gini-measured levels of income inequality compared to other European countries. As measured by the Gini index, Greece as of 2008 had more than income inequality than the economically healthy Germany.[109]

Equitable growth [edit]

While acknowledging the fundamental role economic growth can potentially play in man development, poverty reduction and the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, it is condign widely understood amongst the development community that special efforts must be made to ensure poorer sections of society are able to participate in economic growth.[110] [111] [112] The effect of economic growth on poverty reduction – the growth elasticity of poverty – tin depend on the existing level of inequality.[113] [114] For instance, with low inequality a country with a growth rate of 2% per head and 40% of its population living in poverty, tin halve poverty in 10 years, merely a country with high inequality would accept nearly 60 years to achieve the same reduction.[115] [116] In the words of the Secretarial assistant General of the United Nations Ban Ki-Moon: "While economic growth is necessary, it is non sufficient for progress on reducing poverty."[110] Contest policy intending to prevent companies from abusing market ability contributes to inclusive growth.[117]

Environment [edit]

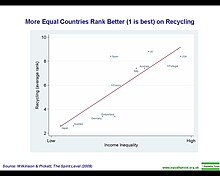

More equal countries rank improve on recycling

Multiple arguments tin can be made most the relationship betwixt poverty and the environment. In some cases, alleviating poverty can result in detrimental environmental affects or exacerbate degradation; the smaller the economic inequality, the more waste product and pollution is created, resulting in many cases, in more ecology degradation. This tin be explained by the fact that as the poor people in the guild become more wealthy, it increases their yearly carbon emissions. This relation is expressed by the Environmental Kuznets Bend (EKC).[118]{ In certain cases, with great economic inequality, there is nonetheless not more waste and pollution created as the waste product/pollution is cleaned up ameliorate afterwards (water treatment, filtering, ... )[119] Also notation that the whole of the increment in environmental degradation is the event of the increment of emissions per person being multiplied past a multiplier. If there were fewer people, yet, this multiplier would be lower, and thus the amount of environmental degradation would be lower as well. Every bit such, the current high level of population has a large touch on this equally well. If (every bit WWF argued), population levels would beginning to drib to a sustainable level (1/3 of electric current levels, and then about two billion people[120]), human inequality can be addressed/corrected, while nevertheless non resulting in an increase of ecology damage.

On the other paw, other sources argue that alleviating poverty will reap positive progressions on the environs, especially with technological advances in energy efficiency. Urbanization, for example, tin "reduce the expanse in which humans impact the environment, thereby protecting nature elsewhere."[121] Through concentration human societies, urbanized regions can permit for more allocated reserves for wildlife. Moreover, through urbanization, such societies have a higher standard of living that can promote environmental health with better food, technology, education, and more. In more than unequal societies, there are stronger drivers for consumerism and stronger belief in free enterprise, and the rich besides use a disproportionate corporeality of resource. Thus, in developed countries, inequality tends to accelerate resource consumption past all classes.[122]

Research also shows that biodiversity loss is higher in countries or in U.s.a. states with higher income inequality.[123]

Political outcomes [edit]

Higher income inequality led to less of all forms of social, cultural, and civic participation among the less wealthy.[124] When inequality is higher the poor exercise not shift to less expensive forms of participation.[125]

In 2015, a study past Lahtinen and Wass suggested that low social mobility reduces turnout among lower classes.[126]

Co-ordinate to a 2017 review study in the Annual Review of Political Scientific discipline by Stanford Academy political scientists Kenneth Scheve and David Stasavage, "the simple conjectures that democracy produces wealth equality and that wealth inequality leads to democratic failure are not supported by the bear witness."[127]

Some, such equally Alberto Alesina and Dani Rodrik, argue that economic inequality creates demand for redistribution and the creation of welfare states.[128] A 2014 study questions this relationship, finding that "inequality did not favour the development of social policy between 1880 and 1930. On the contrary, social policy developed more than hands in countries that were previously more egalitarian, suggesting that unequal societies were in a sort of inequality trap, where inequality itself was an obstacle to redistribution."[129]

War, terrorism and political instability [edit]

One study finds a correlation between income inequality and increased levels of political instability.[130] A 2016 study finds that interregional inequality increases terrorism.[131] Another 2016 report finds that inequality between social classes increases the likelihood of coups merely not civil wars.[132] A lack of reliable data makes information technology difficult to study the relationship betwixt inequality and political violence.[133]

John A. Hobson, Rosa Luxemburg, and Vladimir Lenin argued that WWI was caused by inequality. Economist Branko Milanovic claims that in that location is acceptance to this argument in his 2016 book Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization.[134]

A 2014 study published in Ecological Economic science said that economic stratification of order into "elites" and "masses" played a central office in the collapse of other avant-garde civilizations such as the Roman, Han, and Gupta empires.[135]

Encounter as well [edit]

- Listing of countries past wealth per adult

- Involuntary unemployment

References [edit]

- ^ a b Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, p. 5.

- ^ a b "Happiness: Has Social Scientific discipline A Clue?" Richard Layard Archived June three, 2013, at the Wayback Auto 2003

- ^ a b Blanchard and Oswald 2000, 2003

- ^ a b c More or Less| Branko Milanovic| Finance & Development| September 2011| Vol. 48, No. iii

- ^ De Vogli, R. (2005). "Has the relation between income inequality and life expectancy disappeared? Testify from Italy and top industrialised countries". Periodical of Epidemiology & Customs Wellness. 59 (2): 158–62. doi:ten.1136/jech.2004.020651. PMC1733006. PMID 15650149.

- ^ Kaplan, K. A; Pamuk, E. R; Lynch, J. Westward; Cohen, R. D; Balfour, J. L (1996). "Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: Analysis of mortality and potential pathways". BMJ. 312 (7037): 999–1003. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7037.999. PMC2350835. PMID 8616393.

- ^ Christoffersen, John (October 14, 2013). "Rising inequality 'most important trouble,' says Nobel-winning economist". St. Louis Post-Dispatch . Retrieved Oct 19, 2013.

- ^ "The Spirit Level". equalitytrust.org.uk.

- ^ Pickett, KE; Wilkinson, RG (March 2015). "Income inequality and health: a causal review". Social Science & Medicine. 128: 316–26. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031. PMID 25577953.

- ^ Sapolsky, Robert (2005). "Sick of Poverty". Scientific American. 293 (half-dozen): 92–9. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293f..92S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-92. PMID 16323696.

- ^ Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, p. 82.

- ^ (At the aforementioned time yet, there is a strong connection betwixt average income and health within countries. Example: Comparison average decease rates in United States zip code areas organized past boilerplate income finds the highest income goose egg codes average a piffling over 90 deaths per 10,000, the poorest nada codes a little over fifty deaths and a "strikingly" regular slope of decease rates for income in betwixt. source: Effigy 1.4, Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, p. 13, Authors: "What is so hit about Figure 1.4 is how regular the health gradient is right across society". Data from: Smith, G D; Neaton, J D; Wentworth, D; Stamler, R; Stamler, J (1996). "Socioeconomic differentials in bloodshed adventure among men screened for the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial: I. White men". American Journal of Public Health. 86 (4): 486–96. doi:10.2105/AJPH.86.iv.486. PMC1380548. PMID 8604778. )

- ^ Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, pp. 306–9. Figure 2.two constitute on p. xx and this page

- ^ the authors constitute a Pearson Correlation Coefficient of 0.87 for the index and inequality among xx adult countries for which data was available. Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, p. 310.

- ^ a coefficient of 0.59 for forty US states for which data was available (the index for The states states did non include a component for mobility in its index). For both populations the statistical significance p-value was >0.01. Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, p. 310.

- ^ compare figures ii.6 and two.7 in Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level, 2011, pp. 23–4. Data from An overview of kid well-being in rich countries The United nations Children'south Fund, 2007

- ^ The Spirit Level: how 'ideas wreckers' turned book into political punchbag| Robert Berth| The Guardian| Baronial xiii, 2010

- ^ Kawachi, Ichiro. South.Five. Subramanian. Social Epidemiology. p. 126. [ total commendation needed ]

- ^ "Depression income neighborhood". world wide web.commonwealthfund.org. 2018-09-27. Retrieved 2022-03-07 .

- ^ Burns, Jonathan Chiliad; Tomita, Andrew; Kapadia, Amy Due south (2014). "Income inequality and schizophrenia: Increased schizophrenia incidence in countries with high levels of income inequality". International Periodical of Social Psychiatry. 60 (2): 185–96. doi:10.1177/0020764013481426. PMC4105302. PMID 23594564.

- ^ "Suicides and Drug Overdose Deaths Push Downwards US Life Expectancy". Voice of America. November 29, 2018. Retrieved January xiii, 2019.

William Dietz is with George Washington University in Washington, D.C. He suggested that fiscal struggles, inequality and divisive politics are all depressing many Americans. "I actually do believe that people are increasingly hopeless, and that that leads to drug use, it leads...to suicide," he said.

- ^ Snowdon, Christopher. The spirit level delusion: fact-checking the left's new theory of everything. Piddling Die, 2010.

- ^ Eckersley, Richard. "Across inequality: Acknowledging the complexity of social determinants of health." Social Science & Medicine 147 (2015): 121-125.

- ^ Antony, Jürgen, and Torben Klarl. "Estimating the income inequality-health relationship for the United States betwixt 1941 and 2015: Will the relevant frequencies please stand up?." The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 17 (2020): 100275.

- ^ Leigh, Andrew, Christopher Jencks, and Timothy M. Smeeding. "Health and economic inequality." The Oxford handbook of economic inequality (2009): 384-405.

- ^ Kim, Ki‐tae. "Income inequality, welfare regimes and aggregate health: Review of reviews." International Periodical of Social Welfare 28, no. ane (2019): 31-43.

- ^ Inequality Trust and Political Engagement Eric Uslaner and Mitchell Brown, 2002

- ^ Making Republic Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti, 1993)

- ^ Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community 2000

- ^ Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, 2000, p. 359.

- ^ Albrekt Larsen, Christian (2013). The Rise and Autumn of Social Cohesion: The Structure and De-construction of Social Trust in the US, Uk, Sweden and Kingdom of denmark. Oxford: Oxford University Press[ page needed ]

- ^ The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Club Endangers Our Future, Stiglitz, J.E., (2012) W.Westward. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0393088694[ page needed ]

- ^ Income inequality and homicide rates in Canada and The United Archived October ii, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Neapolitan, Jerome L (1999). "A comparative assay of nations with depression and high levels of violent crime". Journal of Criminal Justice. 27 (three): 259–74. doi:10.1016/S0047-2352(98)00064-6.

- ^ Lee, Matthew R.; Bankston, William B. (1999). "Political structure, economical inequality, and homicide: A cantankerous-national assay". Deviant Behavior. 20 (1): 27–55. doi:x.1080/016396299266588.

- ^ Kang, Songman (2015). "Inequality and offense revisited: Effects of local inequality and economic segregation on crime". Journal of Population Economics. 29 (2): 593–626. doi:10.1007/s00148-015-0579-3. S2CID 155852321.

- ^ Kim, Bitna, Chunghyeon Seo, and Young-Oh Hong. "A Systematic Review and Meta-assay of Income Inequality and Crime in Europe: Practise Places Matter?." European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research (2020): i-24.

- ^ Atems, Bebonchu. "Identifying the Dynamic Effects of Income Inequality on Crime." Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics (2020).

- ^ Corvalana, Alejandro, and Matteo Pazzonab. "Does Inequality Actually Increase Crime? Theory and Evidence." In Technical Report. 2019.

- ^ The Elements of Justice By David Schmidtz (2006)

- ^ Cecil, Arthur. The Economics of Welfare.

- ^ Whitfield, John (28 September 2011). "Libertarians With Antlers". slate.com . Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Milo Vandemoortele 2010. Equity: a central to macroeconomic stability. London: Overseas Evolution Institute

- ^ Slater, John (January nineteen, 2013). "Annual income of richest 100 people enough to end global poverty four times over". Oxfam . Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Khazan, Olga (January xx, 2013). "Can we fight poverty by ending extreme wealth?". The Washington Post . Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ BBC Staff (January 18, 2013). "Oxfam seeks 'new bargain' on inequality from earth leaders". BBC News . Retrieved September 20, 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Hagan, Shelly (Jan 22, 2018). "Billionaires Made And so Much Money Last Twelvemonth They Could End Extreme Poverty 7 Times". Money . Retrieved Dec thirteen, 2018.

- ^ Jared Bernstein (Jan 13, 2014). Poverty and Inequality, in Charts. The New York Times Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Elise Gould (January 15, 2014). No Affair How We Measure Poverty, the Poverty Rate Would Be Much Lower If Economical Growth Were More Broadly Shared. Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ a b De Soto, Hernando (2000). The Mystery of Capital: Why Commercialism Triumphs in the Due west and Fails Everywhere Else. Bones Books. ISBN978-0-465-01614-3. [ page needed ]

- ^ a b c David T Rodda (1994). Rich Man, Poor Renter: A Study of the Relationship Betwixt the Income Distribution and Low Cost Rental Housing (Thesis). Harvard Academy.

- ^ Vigdor, Jacob (2002). "Does Gentrification Harm the Poor?". Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Diplomacy. 2002: 133–182. doi:10.1353/urb.2002.0012. S2CID 155028628.

- ^ Matlack, Janna L.; Vigdor, Jacob L. (2008). "Do ascension tides lift all prices? Income inequality and housing affordability" (PDF). Periodical of Housing Economics. 17 (3): 212–24. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2008.06.004.

- ^ (cited in Matlack Do Rising Tides Lift All Prices? Income Inequality and Housing Affordability, 2006)

- ^ Johnson, Smeeding, Tory, "Economical Inequality" in Monthly Labor review of April 2005, tabular array 3.

- ^ see too "Consumption and the Myths of Inequality", by Kevin Hassett and Aparna Mathur, The Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2012

- ^ a b "Conservative Inequality Denialism," past Timothy Noah The New Commonwealth (October 25, 2012)

- ^ Attanasio, Orazio; Hurst, Erik; Pistaferri, Luigi (2012). "The Development of Income, Consumption, and Leisure Inequality in The The states, 1980–2010". NBER Working Paper No. 17982. SSRN 2035781.

- ^ Congressional Upkeep Part: Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007. October 2011. p. 5

- ^ "The Usa of Inequality, Entry ten: Why Nosotros Can't Ignore Growing Income Inequality," by Timothy Noah, Slate (September 16, 2010)

- ^ The Way Frontward Archived July 11, 2012, at annal.today By Daniel Alpert, Westwood Uppercase; Robert Hockett, Professor of Law, Cornell Academy; and Nouriel Roubini, Professor of Economics, New York University, New America Foundation, October 10, 2011

- ^ Plumer, Brad. "'Trickle-down consumption': How rising inequality tin can leave everyone worse off". 27 March 2013. Washington Post. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Lo, Andrew W. "Reading About the Fiscal Crisis: A 21-Volume Review" (PDF). 2012. Journal of Economical Literature . Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2013. Retrieved Nov 27, 2013.

- ^ Koehn, Nancy F. (July 31, 2010). "A Call to Set the Fundamentals (Review of Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy past Raghuram K. Rajan)". The New York Times . Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Lynn, Barry C.; Longman, Phillip (March–Apr 2010). "Who Bankrupt America'due south Jobs Automobile?". Washington Monthly. March/April 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Castells-Quintana, David; Royuela, Vicente (2012). "Unemployment and long-run economical growth: The role of income inequality and urbanisation" (PDF). Investigaciones Regionales. 12 (24): 153–73. hdl:10017/27066 . Retrieved Oct 17, 2013.

- ^ The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part I, Section III, Affiliate II

- ^ Luxury Fever Archived June 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (extract)| milkeninstitute.org

- ^ Economist Robert Frank at the Commonwealth Club MPR June 26, 2009, 12:00 p.m.

- ^ Galor, Oded (2011). "Inequality, Human being Capital Germination, and the Procedure of Development". Handbook of the Economic science of Education. Elsevier.

- ^ Berg, Andrew Grand.; Ostry, Jonathan D. (2011). "Equality and Efficiency". Finance and Development. International Monetary Fund. 48 (iii).

- ^ Berg, Andrew; Ostry, Jonathan (2017). "Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Money". IMF Economic Review. 65 (4): 792–815. doi:10.1057/s41308-017-0030-8. S2CID 13027248.

- ^ Kaldor, Nicolas (1955). "Alternative Theories of Distribution". Review of Economical Studies. 23 (2): 83–100. doi:10.2307/2296292. JSTOR 2296292.

- ^ a b Galor, Oded; Zeira, Joseph (1993). "Income Distribution and Macroeconomics" (PDF). The Review of Economic Studies. threescore (1): 35–52. doi:10.2307/2297811. JSTOR 2297811.

- ^ a b Galor, Oded; Zeira, Joseph (1988). "Income Distribution and Investment in Man Capital letter: Macroeconomics Implications". Working Paper No. 197 (Department of Economics, Hebrew University).

- ^ The Earth Bank Group (1999). "The Effect of Distribution on Growth" (PDF).

- ^ a b Alesina, Alberto; Rodrik, Dani (1994). "Distributive Politics and Economic Growth". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 109 (two): 65–90. doi:10.2307/2118470. JSTOR 2118470.

- ^ Galor, Oded; Moav, Omer (2004). "From Physical to Man Capital Accumulation: Inequality and the Procedure of Evolution". Review of Economic Studies. 71 (four): 1001–1026. doi:ten.1111/j.1467-937x.2004.00312.10.

- ^ a b Temple, Jonathan (1999). "The New Growth Evidence". Journal of Economic Literature. 37 (1): 112–56. doi:x.1257/jel.37.1.112.

- ^ a b Clarke, George R.G. (1995). "More show on income distribution and growth". Journal of Development Economics. 47 (2): 403–27. CiteSeerX10.i.1.454.5573. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(94)00069-o.

- ^ Baumol, William J. (2007). "On income distribution and growth". Journal of Policy Modeling. 29 (4): 545–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2007.05.004.

- ^ Herzer, Dierk; Vollmer, Sebastian (2013). "Rising elevation incomes do not raise the tide". Journal of Policy Modeling. 35 (4): 504–nineteen. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2013.02.011.

- ^ a b c d e Berg, Andrew K.; Ostry, Jonathan D. (2011). "Equality and Efficiency". Finance and Development. 48 (three). Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Andrew Berg and Jonathan Ostry. (2011) "Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Ii Sides of the Same Coin" Imf Staff Discussion Annotation No. SDN/11/08 (International Monetary Fund)

- ^ Perotti, Roberto (1996). "Growth, income distribution, and democracy: What the data say". Journal of Economic Growth. 1 (2): 149–187. doi:10.1007/bf00138861. S2CID 54670343.

- ^ Barro, Robert J. (2000). "Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries". Periodical of Economic Growth. 5 (ane): 5–32. doi:10.1023/A:1009850119329. S2CID 2089406.

- ^ Ruth-Aida Nahum (February 2, 2005). "Income Inequality and Growth: a Panel Written report of Swedish Counties 1960-2000".

- ^ a b Banerjee, Abhijit V.; Duflo, Esther (2003). "Inequality And Growth: What Can The Data Say?". Journal of Economical Growth. 8 (three): 267–99. doi:10.1023/A:1026205114860. S2CID 4673498. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Kaldor 1955.

- ^ Easterly, William (2007). "Inequality does cause underdevelopment: Insights from a new instrument". Journal of Development Economics. 84 (two): 755–76. CiteSeerX10.1.1.192.3781. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.xi.002.

- ^ Dabla-Norris, Era; et al. (June 2015). Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality: A Global Perspective (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Bagchi, Sutirtha; Svejnar, January (2015). "Does wealth inequality matter for growth? The effect of billionaire wealth, income distribution, and poverty". Journal of Comparative Economics. 43 (three): 505–thirty. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2015.04.002. hdl:10419/89996.

- ^ Stiglitz, Joseph (2009). "The global crisis, social protection and jobs". International Labour Review. 148 (1–2): 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913x.2009.00046.x.

- ^ Thomas Piketty. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press, 2014. pp. 15-16. ISBN 067443000X

- ^ Forbes, Kristin J. (2000). "A Reassessment of the Human relationship betwixt Inequality and Growth". The American Economic Review. 90 (4): 869–87. CiteSeerX10.ane.1.315.86. doi:10.1257/aer.90.4.869. JSTOR 117312.

- ^ Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Swell Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Xx-First Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 374. ISBN978-0691165028.

- ^ Shin, Inyong (2012). "Income inequality and economical growth" (PDF). Economic Modelling. 29 (5): 2049–2057. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.011.

- ^ Muhammad Dandume Yusuf (February 2, 2013). "Corruption, Inequality of Income and economic Growth in Nigeria".

- ^ Staff (December 9, 2014). "Inequality hurts economic growth, finds OECD inquiry". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Pedro Cunha Neves, Óscar Afonso and Sandra Tavares Silva (2016). "A Meta-Analytic Reassessment of the Effects of Inequality on Growth". Earth Development. 78 (C): 386–400. doi:ten.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.038. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ Castells-Quintana, David; Royuela, Vicente (2017). "Tracking positive and negative effects of inequality on long-run growth". Empirical Economics. 53 (iv): 1349–1378. doi:10.1007/s00181-016-1197-y. hdl:2445/54655. S2CID 6489636.

- ^ Brückner, Markus; Lederman, Daniel (2015). "Effects of income inequality on economic growth". VOX CEPR Policy Portal.

- ^ Brückner, Markus; Lederman, Daniel (2018). "Inequality and economic growth: the part of initial income". Journal of Economic Growth. 23 (3): 341–366. doi:10.1007/s10887-018-9156-4. hdl:10986/29896. S2CID 55619830.

- ^ a b Perotti, Roberto (1996). "Growth, Income Distribution, and Democracy: What the Data Say". Journal of Economic Growth. 1 (two): 149–187. doi:10.1007/bf00138861. S2CID 54670343.

- ^ Bénabou, Roland (1996). "Inequality and Growth". NBER Macroeconomics Almanac. xi: eleven–92. doi:x.2307/3585187. JSTOR 3585187.

- ^ Berg, Andrew; Ostry, Jonathan D.; Tsangarides, Charalambos G.; Yakhshilikov, Yorbol (2018). "Redistribution, inequality, and growth: new evidence". Journal of Economical Growth. 23 (3): 259–305. doi:10.1007/s10887-017-9150-2. S2CID 158898163.

- ^ "Is Inequality Necessary?" past Timothy Noah, The New Republic December 20, 2011

- ^ a b Claire Melamed, Kate Higgins and Andy Sumner (2010) Economic growth and the MDGs Overseas Evolution Plant

- ^ Anand, Rahul; et al. (Baronial 17, 2013). "Inclusive growth revisited: Measurement and evolution". VoxEU.org. Heart for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ Anand, Rahul; et al. (May 2013). "Inclusive Growth: Measurement and Determinants" (PDF). Imf Working Paper. Asia Pacific Section: International Budgetary Fund. Retrieved January thirteen, 2015.

- ^ Ranieri, Rafael; Ramos, Raquel Almeida (March 2013). "Inclusive Growth: Edifice up a Concept". 104. hdl:10419/71821.

- ^ Bourguignon, Francois, "Growth Elasticity of Poverty Reduction: Explaining Heterogeneity across Countries and Fourth dimension Periods" in Inequality and Growth, Ch. ane.

- ^ Ravallion, M. (2007) Inequality is bad for the poor in South. Jenkins and J. Micklewright, (eds.) Inequality and Poverty Re-examined, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ Elena Ianchovichina and Susanna Lundstrom, 2009. "Inclusive growth analytics: Framework and awarding", Policy Research Working Paper Serial 4851, The Earth Bank.

- ^ Fabienne, Ilzkovitz; Dierx, Adriaan (June 19, 2016). "Competition policy and inclusive growth". VOX European union. CEPR. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ "Unexpected connections: Income inequality and environmental degradation". shapingtomorrowsworld.org. 2012-02-13.

- ^ WWF's sustainability and equality paper

- ^ "WWF – Living Planet Report". panda.org.

- ^ Clemente, Jude. "Urbanization: Reducing Poverty and Helping the Environment". Forbes . Retrieved February nineteen, 2018.

- ^ Dorling, Danny (4 July 2017). "Is inequality bad for the environment?". The Guardian . Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Mikkelson, Gregory (2007). "Economical Inequality Predicts Biodiversity Loss". PLOS One. 2 (5): e444. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..444M. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0000444. PMC1864998. PMID 17505535.

- ^ Bram Lancee and Hermanvande Werfhorst (2011) "Income Inequality and Participation: A Comparison of 24 European Countries" GINI Discussion Paper No. 6 (Amsterdam Middle for Inequality Studies)

- ^ The Equality Trust (2012) "Income Inequality and Participation" [ permanent dead link ] Research Update No. 4

- ^ Lahtinen, Hannu; Wass, Hanna; Hiilamo, Heikki (2017). "Gradient constraint in voting: The effect of intra-generational social class and income mobility on turnout" (PDF). Balloter Studies. 45: 14–23. doi:ten.1016/j.electstud.2016.eleven.001. hdl:10138/297763.

- ^ Scheve, Kenneth; Stasavage, David (2017). "Wealth Inequality and Democracy". Annual Review of Political Science. 20 (1): 451–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-061014-101840.

- ^ Alesina, A.; Rodrik, D. (1994). "Distributive Politics and Economic Growth". The Quarterly Journal of Economics (Submitted manuscript). 109 (2): 465–90. doi:10.2307/2118470. JSTOR 2118470.

- ^ Espuelas, Sergio (2015). "The inequality trap. A comparative analysis of social spending between 1880 and 1930". The Economic History Review. 68 (2): 683–706. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.12062. hdl:2445/107808. S2CID 11900803.

- ^ Alesina, Alberto; Perotti, Roberto (1996). "Income distribution, political instability, and investment". European Economical Review (Submitted manuscript). 40 (6): 1203–28. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(95)00030-5. S2CID 51838517.

- ^ Ezcurra, Roberto; Palacios, David (2016). "Terrorism and spatial disparities: Does interregional inequality matter?". European Journal of Political Economy. 42: 60–74. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.01.004.

- ^ Houle, Christian (2016). "Why class inequality breeds coups but not civil wars". Journal of Peace Research. 53 (v): 680–95. doi:10.1177/0022343316652187. S2CID 113899326.

- ^ "It's Harder Than Information technology Looks To Link Inequality With Global Turmoil". FiveThirtyEight. 2016-01-07. Retrieved Jan viii, 2016.

- ^ Milanovic, Branko (2016). Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Historic period of Globalization. Harvard University Press. p. 96. ISBN978-0674737136.

- ^ Motesharrei, Safa; Rivas, Jorge; Kalnay, Eugenia (2014). "Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): Modeling inequality and utilise of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies". Ecological Economics. 101: xc–102. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.02.014.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effects_of_economic_inequality

0 Response to "Inequality a Reassessment of the Effects of Family and Schooling in America"

Post a Comment